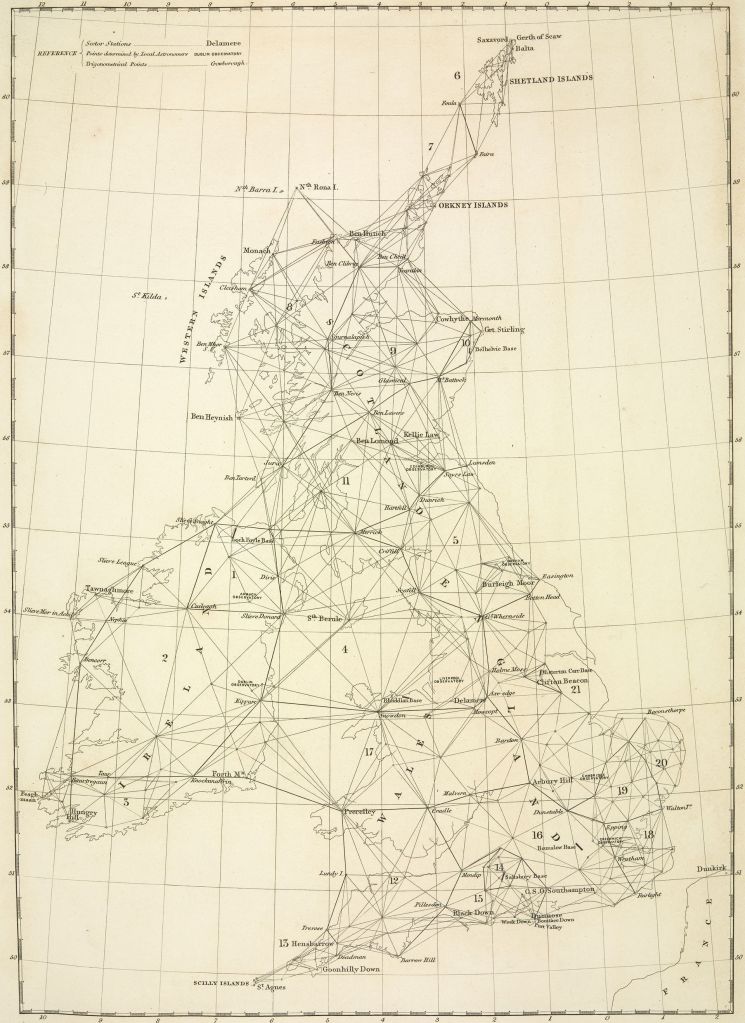

For those of us, who grew up in the UK with real maps printed on paper, rather than the online digital version offered up by Google Maps, the Ordnance Survey has been delivering up ever more accurate and detailed maps of the entire British Isles since their original Principal Triangulation of Great Britain carried out between 1791 and 1853.

Supplied with this cartographical richness it is easy to forget that England and Scotland once had separate mapping histories, before James VI & I[1] became monarch of both countries in 1603, and later the Act of Union in 1707, joined them together as one nation.

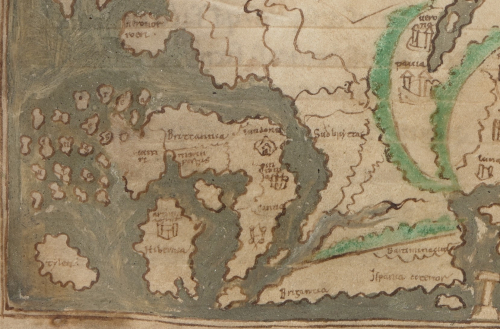

Rather bizarrely, the Ptolemaic world map rediscovered in Europe in the fifteenth century but originating in the second century CE gives an at least recognisable version of England but with Scotland turned through ninety degrees, pointing to the east rather than the north.

The same image can be found on a world map from the eleventh century in the manuscript collection of Sir Robert Cotton (1570/1–1631).

The most developed of the maps of Britain drawn by the monk Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1259), also in the Cotton manuscript collection, has Scotland north of England but very strangely divided into two parts north of the Antonine Wall joined by a bridge at Stirling.

Whereas on Matthew Paris’ map, the northern part of Scotland is only attached by the bridge at Stirling, on the Hereford Mappa mundi from c. 1300, Britain looks like a shapeless slug squashed down into the northwest corner of the map with Scotland, a separate island, floating to the north.

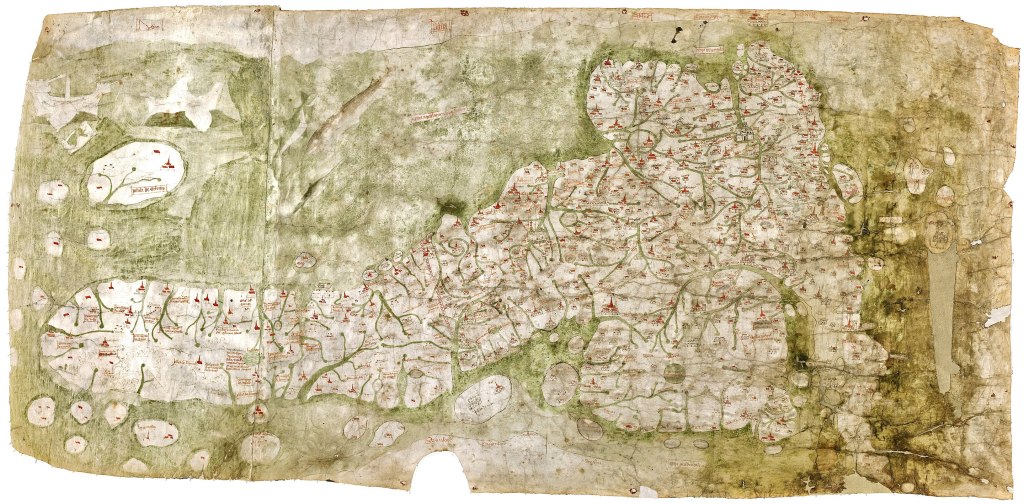

On the medieval Gough Map, the date of which is uncertain, with estimates varying between 1300 and 1430, Scotland, whilst hardly recognisable, had at least achieved its true north pointing orientation, although the map itself has east at the top.

The version of Britain on the Ptolemaic, the eleventh century Cotton, and the Hereford world maps show almost no details. Matthew Paris’ map is part of a pilgrimage itinerary and shows the towns on route and very prominently the rivers but otherwise very little detail. The Gough map, like the Paris map emphasises towns rivers and route. Also compared to the Ptolemaic map, its depictions of the coastlines of England and Wales are much improved. However, its depiction of the independent kingdom of Scotland is extremely poor.

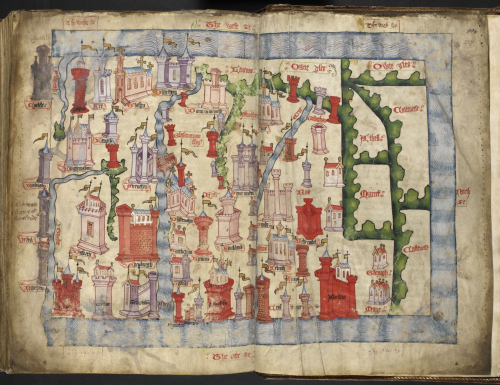

All the maps presented so far show Scotland in a much wider geographical context, part of the world or part of Britain. The oldest known existing single map of Scotland was created by John Hardyng (1378–1465) an English soldier turned chronicler, who set out to prove that the English kings had a right to rule over Scotland. As part of the fist version of his Chronicle of the history of Britain, which he presented to King Henry VI of England, in a failed attempt to instigate an invasion of Scotland, he included a strangely rectangular map of Scotland with west at the top and north to the right.

As can be seen, this map contains much more detail of the Scottish towns, displaying castles and walls, as well as in two cases churches instead.

The next map of Scotland was produced by the English antiquarian, cartographer, and early scholar of Anglo-Saxon and literature, Laurence Nowell (1530–c. 1570) in the mid 1560s. Around the same time he produced a pocket-sized map of Britain entitled A general description of England and Ireland with the costes adioyning for his patron Sir William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (1520–1598) Elizabeth I chief adviser.

His map of Scotland, with west at the top, is much more detailed than any previous maps and bears all the visual hallmarks of comparatively modern mapmaking.

With Nowell we have entered the Early Modern Period and the birth of modern mapmaking in the hands of Gemma Frisius (1508–1555), who published the first account of triangulation in 1533, Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598) creator of the first modern atlas[2] in 1570, and Gerard Mercator (1512–1594) the greatest globe and mapmaker of the century. As I have already detailed in an earlier post, England lagged behind the continental developments, as in all of the mathematical disciplines.

Burghley motivated and arranged sponsorship for other English mapmakers, which led to the publication of the first English atlas, created by Christopher Saxton (c. 1540–c. 1610), in 1579, following a survey, which took place from 1574 to 1578. Scotland was at this time still an independent country, so Saxton’s atlas only covers the counties of England and Wales.

Various projects were undertaken to improve the quality of Saxton’s atlas of which, the most successful was by the John Speed (1551/2–1629), who published his The Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine, which was dated 1611, in 1612. By now James had been sitting on the throne on both countries for nine years, however, Speed’s Theatre only contains a general map of Scotland and not detailed maps of the Scottish counties.

Why was this? The annotations to the facsimile edition of Speed’s Theatre give two reasons for this. Firstly, the book was originally conceived in 1590, when the two kingdoms were still independent of each other, and it was production delays that led to the later publication date, when modification to include the Scottish counties would have led to further delays. However, in our context, the mapping of Scotland, it is the second reason that is more interesting:

Secondly, Speed knew of the Scotsman Timothy Pont’s work in surveying Scotland. The have extended the Theatre to include maps for Scotland similar to those for England, Wales and Ireland would have been to duplicate Pont’s efforts, even if cartographical aspects were differently emphasised by the two men.[3]

We have now reached the title topographer of this blog post, Timothy Pont (c. 1560–c. 1614), who was he and why is there no Pont’s Atlas of Scotland?

Timothy Pont was the first person to make an almost complete topographical survey of Scotland. Unfortunately, as with many people from the Early Modern Period, we only have a sketchy outline of his life and no known portrait, in fact we know far more about his father, Robert Pont (1529–1606), a minister, judge, and reformer, an influential legal, political, and religious man, who rose to be Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, in 1575. Timothy was his eldest child by his first wife Catherine daughter of Masterton of Grange, with whom he had two sons and two daughters[4]. By his second wife Sarah Denholme he had one daughter and by his third wife Margaret Smith he had three sons.

In 1574 Timothy received an annual grant of church funds from his father, he matriculated at the University of St Andrews in 1508 and graduated M.A. in 1583. It was possibly at St Andrews that he learnt the art of cartography, but it is not known for certain. It is not known when he carried out his survey of Scotland. Only his map of Clydesdale contains a date, (Sept. et Octob: 1596 Descripta) and it appears he ended his travels around this time and that he began them after graduating from St Andrews.

Somewhat earlier in 1592, he had received a commission to undertake a mineral reconnaissance of Orkney and Shetland, so his activities were obviously known. In 1593 his father again supported him financially, assigning him an annuity from Edinburg Town Council.

His wanderings and topographical activities apparently terminated, in 1600 Timothy was appointed minister of the parish of Dunnet in Caithness. He is recorded as having visited Edinburg in 1605. In 1609, he applied unsuccessfully for a grant of land in the north of Ireland. There is evidence that he was still Parson of Dunnet in 1610 but in 1614 another held the post, and in 1615, Isabel Pont is recorded as his widow both facts indicating that he had died sometime between 1611 and 1614. Unfortunately, as is often the case with mapmakers in the Early Modern Period, we have no real information as to how Pont carried out his surveys or which methods he used.

We now turn to Pont’s activities as a topographer and mapmaker. Pont never finished his original project of producing an atlas of Scotland. Only one of Pont’s maps, Lothian and Linlithgow,

was engraved during his lifetime, by Jodocus Hondius the elder in Amsterdam,

sometime between 1603 and 1612. However, the map, dedicated to James VI &I, was first published in the Hondius-Mercator Atlas in 1630. In a letter from 1629, Charles I wrote in a letter that his father had intended to financially support Pont’s project and granted the antiquarian Sir James Balfour of Denmilne (1600-1657), the Lord Lyon King-of-Arms, who had acquired the maps from Pont’s heirs, money to plan the publication of the maps.

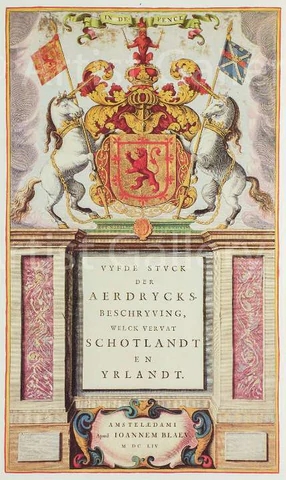

At this point Sir John Scot, Lord Scotstarvit (1585-1670) entered the story. Already a correspondent of Willem (1571–1638) and Joan Blaeu (1596–1679), of the Amsterdam cartographical publishing House of Blaeu, he informed them of Balfour’s acquisition of Pont’s topographical survey of Scotland, Willem Blaeu having already asked Scot about maps of Scotland in 1626. Through Scot’s offices Pont’s maps made their way to Amsterdam. What then followed is briefly described by Joan Blaeu in his Atlas Novus in 1654.

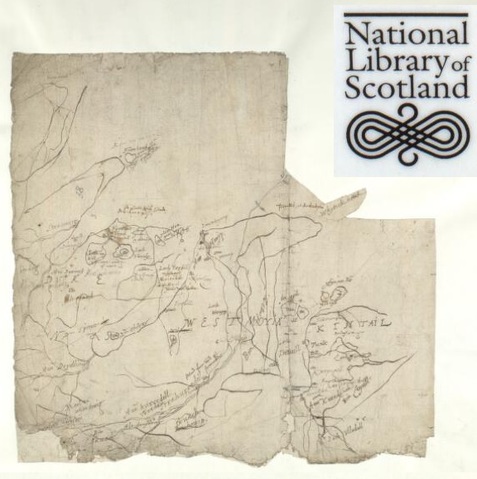

Scot collected them and other maps and sent them over to me but much torn and defaced. I brought them into order and sometimes divided a single map. into several parts. After this Robert and James Gordon gave this work the finishing touches. and added thereto, besides the corrections in Timothy Pont’s maps, a few maps of their own.

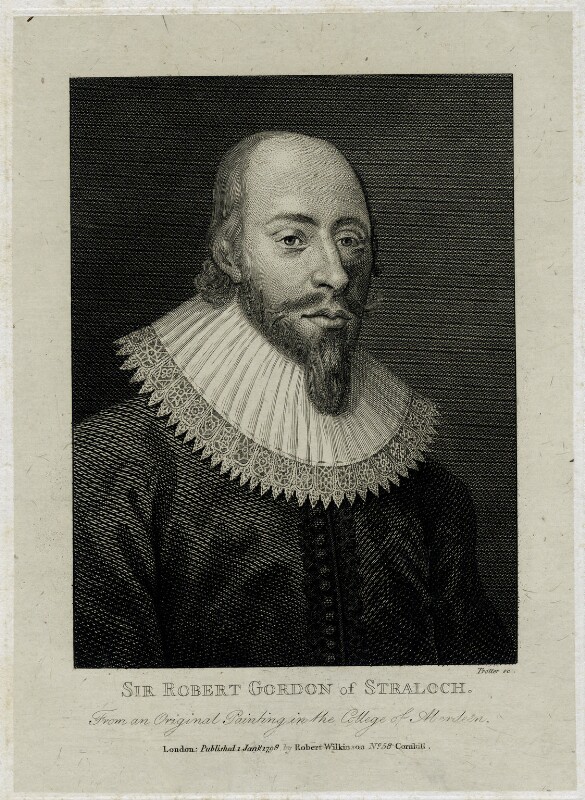

Robert Gordon of Straloch (1580–1661) and his son James Gordon of Rothiemay (c. 1615–1686) were Scottish mapmakers, who obviously played a central role in preparing Pont’s maps for publication.

Robert was called upon to undertake this work by Charles I in a letter from 1641; Charles entreated him “to reveis the saidis cairtiss”. Acts of parliament exempted him from military service, whilst he undertook this task and the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland published a request to the clergy, to afford him assistance.

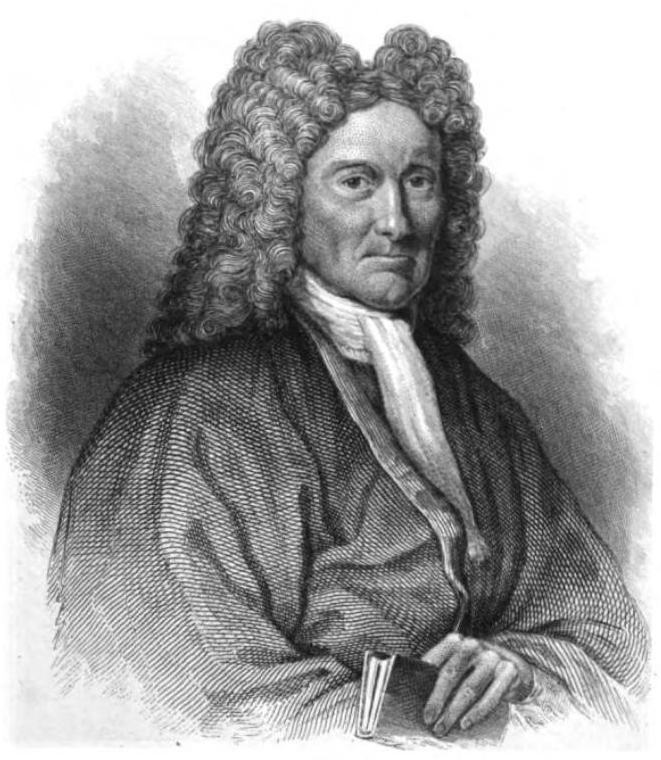

The exact nature of the role undertaken by Robert and James Gordon in the revision of the maps is disputed amongst historians and I won’t go into that discussion here. However, following his father’s death in 1661, James preserved all of Pont’s surviving maps, along with his and his father’s own cartographical work and passed them on to the Geographer Royal to Charles II, Sir Robert Sibbald (1641–1722), in the 1680s. Sibbald’s own papers along with the Pont maps were placed in the Advocates Library following his death in 1772. The Advocates Library became the National Library of Scotland, where Pont’s maps still reside[5].

As already indicated above Pont’s maps formed the nucleus of Joan Blaeu’s Atlas of Scotland, the fifth volume of his Theatrum Orbis Terrarum sive Atlas Novus published in Amsterdam in Latin, French, and German in 1654.

This was the first atlas of Scotland, and it wasn’t really improved on in any way until the military survey of Scotland carried out by William Roy (1726–1790) between 1747 and 1755. Roy would go on to be appointed surveyor-general and his work and lobbying led to the establishment of the Ordnance Survey, whose Principal Triangulation of Great Britain, mentioned at the beginning of this post, began in 1791, one year after his death.

My attention was first drawn to Pont’s orthographical survey of Scotland by advertising for a new permanent exhibition “Treasures of the National Library of Scotland”, which prominently features Pont’s maps, so I went looking for the story of this elusive mapmaker.

[1] For any readers confused by James VI & I, he was James VI of Scotland and James I of England

[2] This and other uses of the term atlas here are anachronistic as Mercator first used the term in the title of his Atlas, sive cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mundi published in 1585

[3] The Counties of BRITAIN: A Tudor Atlas by John Speed, Introduction by Nigel Nicolson, County Commentaries by Alasdair Hawkyard, Published in association with The British Library, Pavilion, London 1998, p. 265

[4] I can’t resit noting that Timothy’s youngest sister, Helen, married an Adam Blackadder!

[5] The National Library of Scotland has an extensive website devoted to Pont and his maps from which much of the information for this blog post was culled

Thanks for the very informative article. Wonderful!

Excellent article as always.

Matthew Paris’ map is part of a pilgrimage itinerary and shows the towns on route and very prominently the rives but otherwise very little detail.

Do you mean rivers ?

Probably 👀

> with Scotland turned through ninety degrees, pointing to the east rather than the north… The same image can be found on a world map from the eleventh century in the manuscript collection of Sir Robert Cotton

I don’t see that at all. Scotland on this map is a collection of islands with a little bit of mainland south of them, but it’s pointing north?